The Atacama Serpent: Unearthing a Prehistoric Leviathan in the Chilean Desert

The year is 1998. Dr. Elena Ramirez, a paleontologist whose sun-weathered face bore the marks of countless desert expeditions, squinted against the relentless glare of the Atacama Desert. For weeks, her team had been mapping anomalous seismic readings near the desolate Quebrada de la Vaca, a region of Chile known more for its lunar landscape than its prehistoric treasures. Today, however, was different.

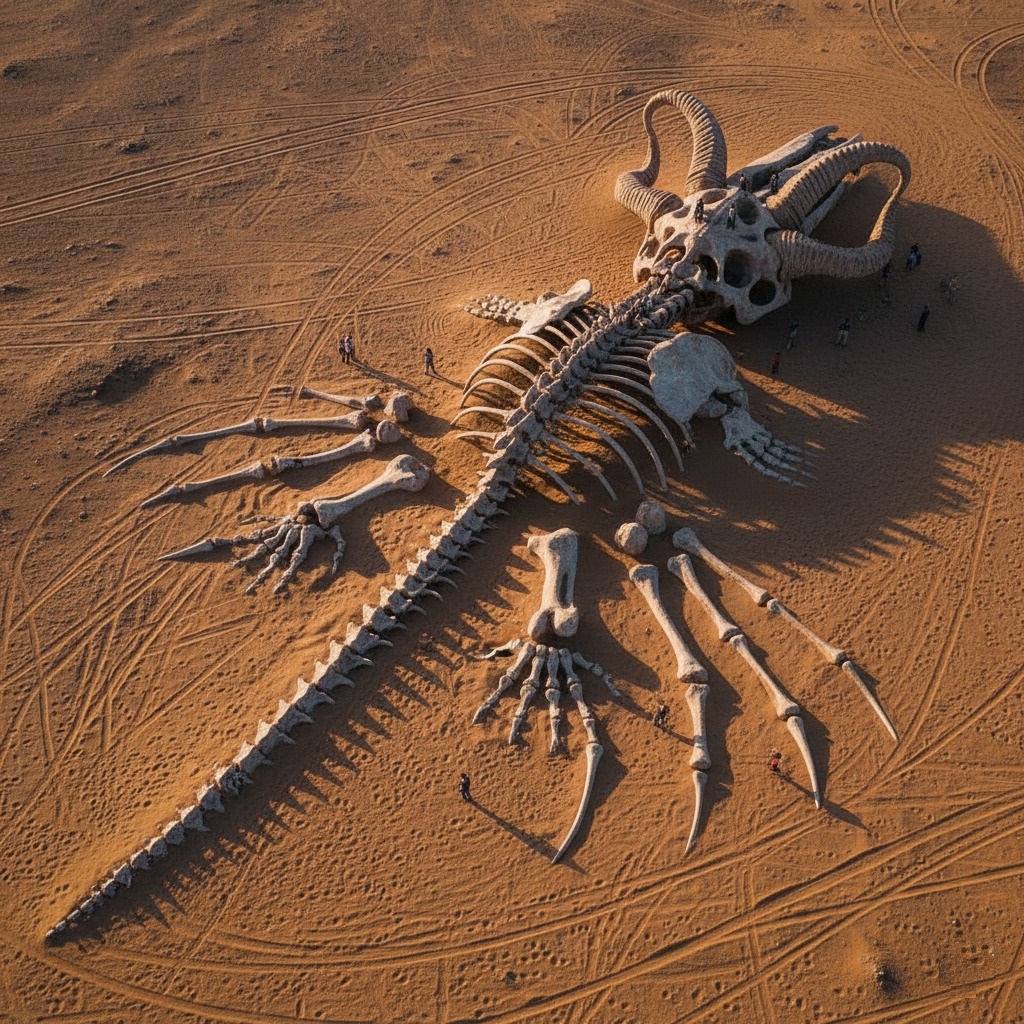

From their small, rented Cessna, what had initially appeared as a peculiar geological formation on satellite imagery now resolved into something impossibly grand. “My God,” Elena breathed, her voice barely a whisper above the engine’s drone. Below them, stretching for nearly a kilometer across the ochre sands, lay an articulated skeleton of such immense proportions it defied immediate classification. It was a serpent, but a serpent unlike any known to science, its bleached bones curving majestically, an ancient guardian slumbering beneath the unyielding sun.

The initial descent was a flurry of activity. Graduate students, their faces a mixture of disbelief and awe, carefully marked the perimeter. The sheer scale was overwhelming; individual vertebrae were as large as truck tires, and the skull, situated at the serpent’s head, was a fortress of bone, hinting at a creature of formidable power. Dr. Ben Carter, the team’s geochronologist, quickly set up ground-penetrating radar, his instruments confirming that the bones lay just beneath a thin layer of sand, remarkably preserved by the desert’s extreme aridity.

As days bled into weeks, the Atacama Serpent began to yield its secrets. Carbon dating placed the leviathan in the Late Cretaceous period, a time when the Atacama, now one of the driest places on Earth, was a verdant coastal region teeming with marine life. This creature, Elena hypothesized, was a colossal marine reptile, an apex predator that once ruled ancient seas. Its placement, so far inland, suggested a dramatic geological shift or perhaps a catastrophic event that had stranded its immense carcass as the land rose.

One evening, as the desert sky exploded in a riot of purples and oranges, Elena stood by the massive skull, tracing the contours of its eye sockets. The fossil didn’t just represent an extinct species; it was a window into a lost world, a testament to the Earth’s dynamic past. The discovery at Quebrada de la Vaca wasn’t merely a paleontological triumph; it was a profound reminder of the planet’s ever-changing face, and the ancient, magnificent creatures that once roamed its forgotten corners. The Atacama Serpent, now carefully being excavated and studied, was poised to rewrite chapters of prehistoric marine biology, forever etched into the annals of scientific discovery.