The Substance

Twisted, Original, and Unapologetically Grotesque.

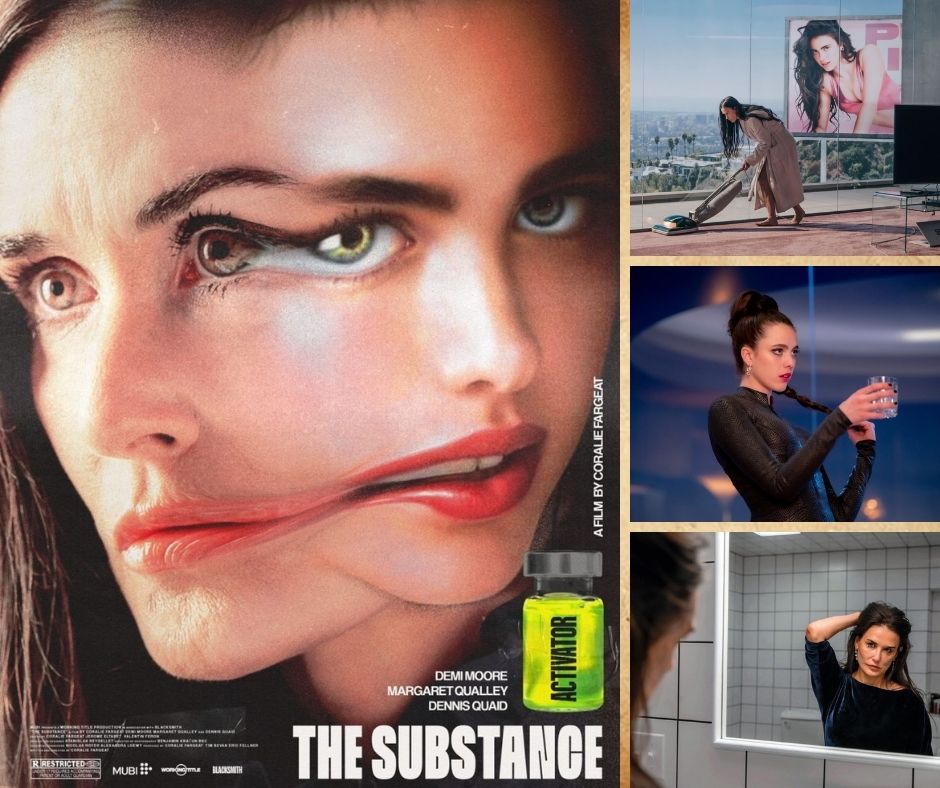

Of all the well-earned praise The Substance deserves, none is more fitting than recognizing it as a directorial triumph. With only her second feature film, French director Coralie Fargeat cements herself as a visionary, orchestrating a cinematic experience that is both unrelenting and meticulously controlled. From the outset, there’s an undeniable sense that we’re witnessing something destined to leave a mark—something that will be remembered. Every scene feels deliberate, every shock calculated, as Fargeat plays with audience expectations, pushing the film further and further into excess. Just when it seems to have reached its peak, it escalates again. And again. She wields every tool at her disposal with razor-sharp precision—editing that jolts at just the right moments, sound design that amplifies unease, and flawless casting. Every choice feels intentional, every element fine-tuned to maximize the film’s impact. The result is an unhinged yet masterfully constructed descent into body horror and industry satire, a film so bold and unpredictable that its recognition by the Academy—earning five nominations, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actress, and Best Original Screenplay—is both surprising and deeply satisfying.

With a concept that feels straight out of a Black Mirror episode, the film follows Elisabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore), a once-glamorous Hollywood actress who, at 50, is clinging to the last remnants of her career. Desperate to reclaim her fading spotlight, she turns to a black-market medical procedure involving a mysterious substance that creates a younger, perfected version of herself—Sue (Margaret Qualley). However, the substance demands perfect balance: one week as Elisabeth, one week as Sue.

The film tells its story primarily through visuals, expressions, and silence. Dialogue is sparse—characters rarely speak—but their emotions are always clear. Fargeat fills the film with clever visual ideas that leave a far stronger impact than words ever could. From the very first shot—a time-lapse of Elisabeth’s once-shiny star on the Walk of Fame cracking and deteriorating—to the subtle ways her home changes over time, or even the distinct way Sue laughs, the film conveys its themes through striking imagery. The first half, while rooted in its inventive concept, remains relatively grounded (aside from its stylized camerawork). But as the film progresses, it gradually shifts from heightened reality into full-blown absurdity and excess.

Subtlety is in short supply. As Elisabeth/Sue’s pursuit of beauty spirals out of control, The Substance plunges headfirst into body horror territory. Once it crosses that line, it never looks back, pulling no punches as it builds toward a third act that is as nightmarish as it gets.

Using exceptional practical makeup effects, The Substance features transformation sequences that are both grotesque and deeply unsettling. But it’s what the film puts its actresses through that will make the squeamish want to flee. It’s impressive how the makeup can be so disturbingly grotesque yet, at times, darkly comedic—remaining just believable enough within the film’s heightened reality. The Academy rightfully recognized this giving the film its sole Oscar win.

Fargeat’s casting choices are another major achievement. Not only do both lead actresses fully commit to the physical and psychological demands of the film—throwing themselves to the ground, screaming, and exposing their bodies—but their real-life personas add another layer to their performances. Demi Moore, once one of Hollywood’s biggest stars, hasn’t had a major leading role in years, and that history subtly informs her portrayal of Elisabeth’s desperation. Meanwhile, Qualley embodies Sue with the hungry ambition of someone on the verge of becoming the next big thing. Dennis Quaid, on the other hand, is clearly having the time of his life playing a sleazy, larger-than-life studio producer—named Harvey, for reasons that need no explanation.

However, despite its strengths, The Substance falters in areas where it could have deepened its impact. As the second half unfolds, it becomes increasingly clear that certain sequences exist more for their visual spectacle than for meaningful narrative progression. It relies too heavily on nightmare sequences to amplify its horrors, and not all of its narrative choices contribute meaningfully to the film’s themes. A pivotal late-stage transformation, for instance, would have carried greater weight had it emerged not from necessity but from Sue’s own obsessive drive to push even further toward unattainable perfection.

But the film’s biggest shortcoming is the lack of a convincing link between Qualley and Moore’s performances. Sue is supposed to be an idealized version of Elisabeth, but beyond their physical resemblance, little effort is made to establish a deeper connection between the two. The film repeatedly tells us that Sue is Elisabeth, but we never truly feel it.

Yet, despite these flaws, The Substance delivers a third act so wildly audacious and technically impressive that it elevates the entire film into something unforgettable. It may not be particularly nuanced in its critique, but its sheer ambition, inventiveness, and visceral execution ensure its longevity. A bold, bizarre, and visually arresting exploration of fame, identity, and self-worth, The Substance is a film that demands to be seen—and endured.