The Siren of Santorini: Unearthing the Aegean’s Ancient Mermaid

The late afternoon sun, a molten disc above the Aegean, cast long, dramatic shadows across the excavation site on Santorini. Dr. Aris Thorne, head archaeologist for the Hellenic Ministry of Culture, wiped a bead of sweat from his brow, his gaze fixed on the anomaly emerging from the volcanic soil. For weeks, his team had been meticulously uncovering what they believed was a previously unknown Minoan settlement, predating the devastating Bronze Age eruption that reshaped the island. Pottery shards, obsidian tools, and fragments of frescoes had filled their daily logs. But this… this was unprecedented.

“Careful, Eleni,” he murmured, his voice hushed with a reverence usually reserved for Mycenaean gold masks. His junior assistant, Eleni Petros, a brilliant young paleobotanist with an uncanny eye for detail, was painstakingly brushing away centuries of volcanic ash and compacted earth. Beneath her delicate touch, something truly extraordinary was revealing itself.

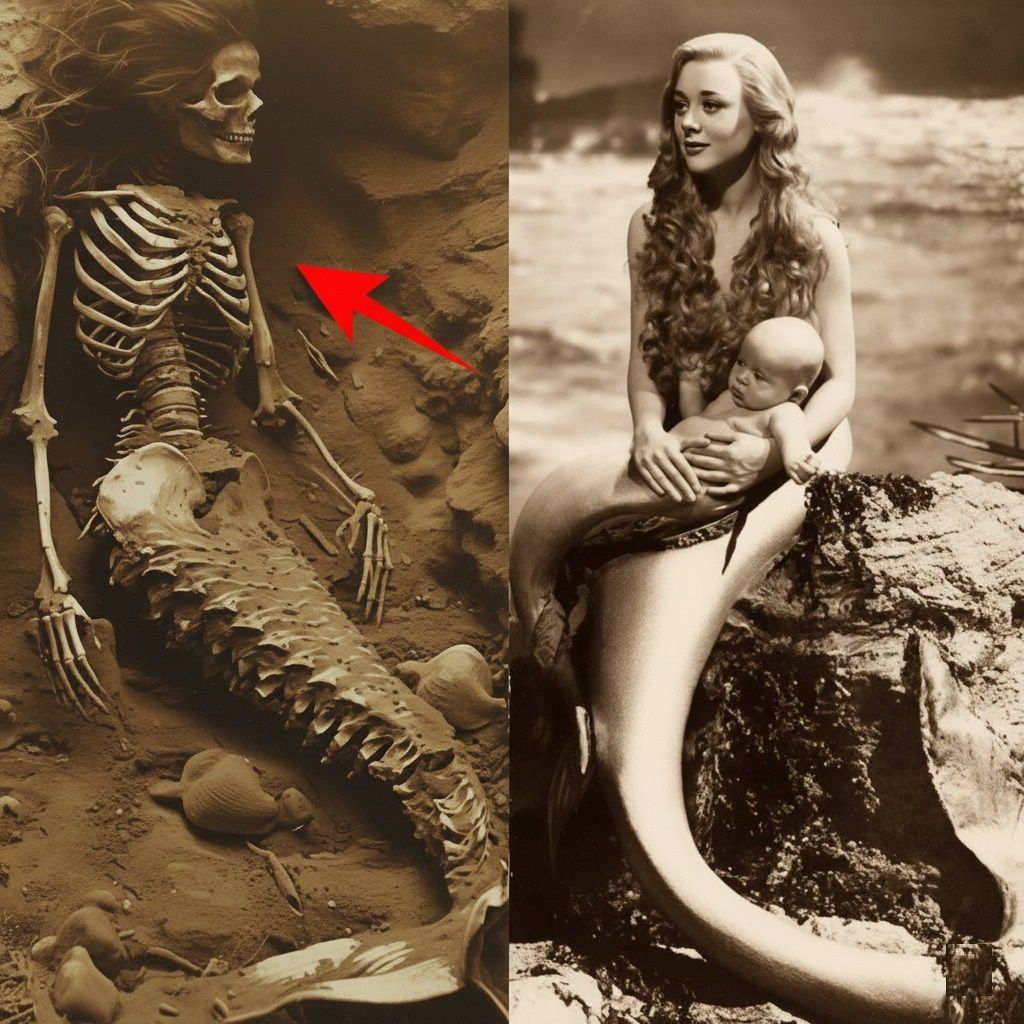

It was a skeleton, undeniably ancient, preserved with an eerie completeness by the very catastrophe that had buried it. But this was no ordinary human. The upper torso, with its delicate ribcage and distinctly human skull, transitioned seamlessly into a long, articulated caudal fin – a mermaid. An actual mermaid. Dr. Thorne felt a shiver, a mix of scientific awe and childlike wonder, crawl down his spine. The iconic red arrow, metaphorically speaking, pointed directly at the impossible truth now laid bare before them, a truth that would shatter paleontology and rewrite mythology.

Back in his tent, under the flickering light of a gas lamp, Aris Thorne pored over ancient texts. The legends of sirens and nereids, often dismissed as folklore, suddenly took on a terrifying new dimension. Had the Minoans of Akrotiri lived alongside such beings? Had the colossal tsunami that followed the eruption claimed more than just human lives? The implications were staggering, promising to redefine not just Aegean history, but the very understanding of life on Earth.

Years later, a different kind of image would emerge, one that whispered of the Siren’s life, not her death. Found amongst a forgotten collection of early 20th-century ethnographic photographs in an archive in Athens, a sepia-toned portrait surfaced. It depicted a woman, her hair cascading in wild curls, eyes sparkling with an ancient, knowing light, cradling an infant. Her lower half was unmistakably a shimmering, elegant tail, sculpted by the artist to perfectly capture the grace of the sea. She sat on a rocky outcrop, reminiscent of Santorini’s rugged coastline, the vast, shimmering Aegean behind her.

This photograph, a carefully staged theatrical piece from the Golden Age of Greek cinema, served as an artistic echo of the archaeological marvel found millennia later. It was a visual representation, perhaps a longing, for the myth the Santorini skeleton had now brought to life. Dr. Thorne, now an internationally renowned figure, often held the two images side-by-side: the stark, undeniable reality of bone and earth on one hand, and the poetic, hopeful artistry of life on the other. Both, in their own way, told the story of the Siren, forever woven into the geological and cultural fabric of Santorini.